Longtermism in 1888: fermi estimate of Heaven's size

To comment or view community discussion of this article, see the cross-posted version on the EA Forum.

While investigating a box of old family letters over thanksgiving, I unexpectedly came across a bizarre Christian-longtermist argument about the future duration of human civilization. The brief letter describes a calculation made by my great-great-grandfather William Quinn in 1888, although it reads more like something out of a Ted Chiang science-fiction anthology. It’s hard to tell if the estimate is serious — it was probably made with at least some of the same joking spirit as the modern-day thermodynamics story about why “heaven is hotter than hell”. I am posting it here for your enjoyment and consideration – I’m sure that my great-great grandfather would have been very pleased to know that its ideas would be shared, one hundred and thirty-three years later, among a community of like-minded philosophers and thinkers.

The Calculation

My great-great grandfather starts from a line in Revelations that purports to give the volume of heaven (12,000 furlongs in every direction, which comes out to about fourteen quintillion cubic meters), then walks through a familiar fermi-estimate style of reasoning: if 25% of the volume is devoted to habitable rooms (as opposed to roads, palaces, gardens, etc), and if rooms are a plausible size, then there will be about 1.2∗1020 total rooms in heaven.

My ancestor then employs an extremely dubious approximation of human population growth — “we will suppose the world did and always will contain nine hundred million inhabitants”. (Really he ought to have known better, considering that he and his wife had a preposterous eleven children of their own!) Since generations are about 30 years apart, this gets you about three billion lives per century.

Finally, he compares the size of heaven to the population of earth. Heaven seems quite capacious — even if there were a hundred other worlds like ours (other planets, perhaps) all feeding into the same Heaven, and even if all these civilizations lasted one million years in duration, there would still be enough space for each inhabitant of Heaven to enjoy a personal mansion of over 100 rooms.

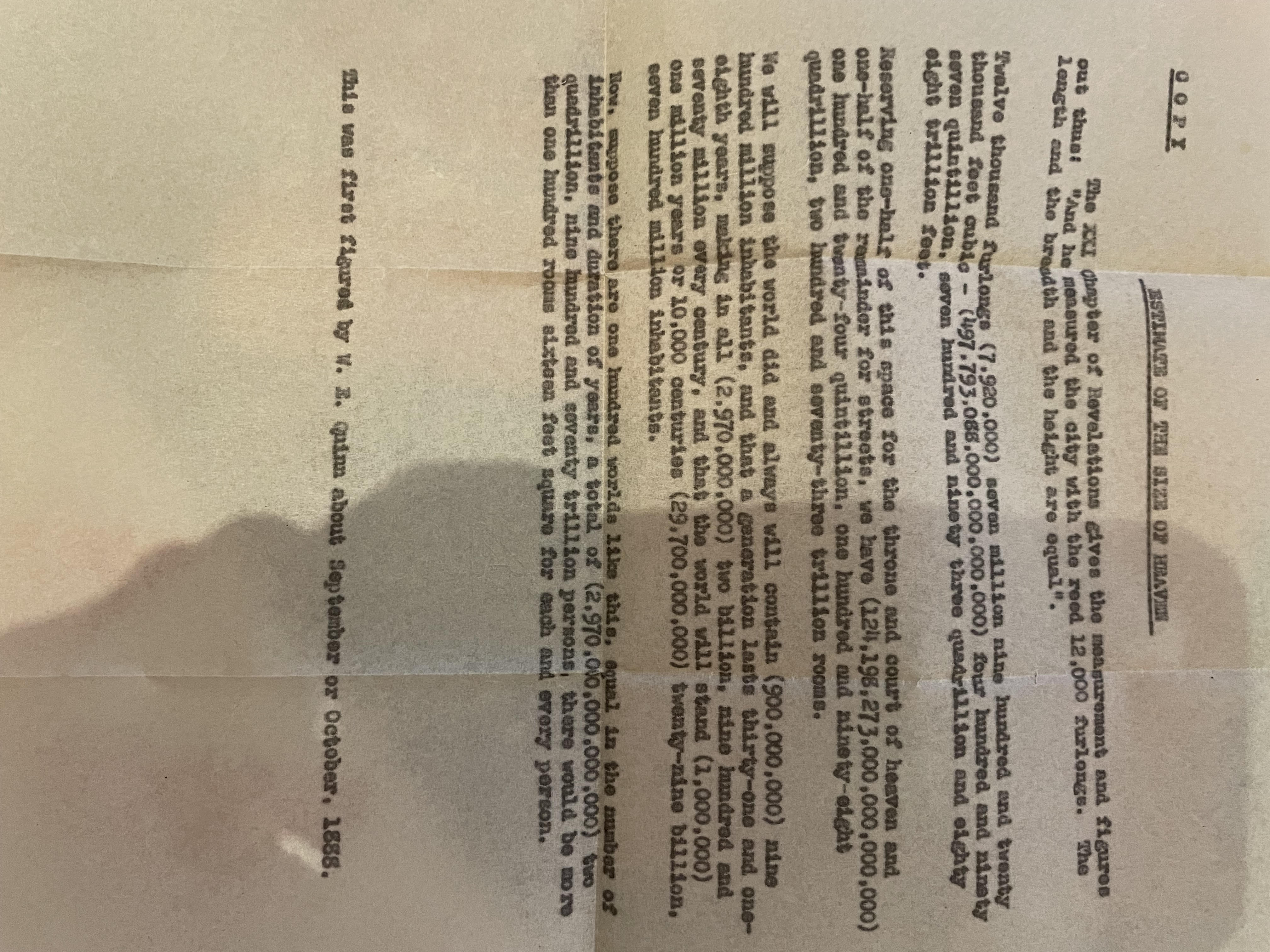

Here is a picture of the letter as I found it last month:

Reflections

Besides my surprise at seeing such a wild metaphysical estimate coming out of rural 1880s Louisiana, this gave me a moment of interesting perspective about similar efforts at long-term predictions made today. I find it inspiring and heartwarming to think that humans have always asked big philosophical questions of the sort that concern longtermist and utilitarian philosophies. But of course, it also gives me pause that the proposed answers to such questions have often been wildly wrong and hopelessly confused. With the progress of science and civilization, we certainly see much farther now than most of our great-great-grandfathers did, but our own ideas about the far future might still end up looking just as silly when compared to however reality actually turns out.

A commenter at the EA Forum also observes:

He as well as any readers of this letter would have greatly benefited from scientific notation! That makes me wonder what terrible inefficiencies in communication and encoding / expressing ideas we’re suffering from today, without having any inkling that things could be better…

Finally, the letter (joking as it may be), also strikes me as perhaps reflecting the Christian attitude, described in this 80,000 Hours episode, that human extinction was impossible for various reasons — because God had promised not to destroy the world, or because mere mankind could never possess for itself the godlike power to destroy the world, or because specific future events had been promised to occur (how could Christ fulfill his promise of return if there was only a dead wasteland to return to?), or as here because Heaven was so capacious that it implied a million-year lifetime for civilization. Their confidence in Christian civilization’s “existential security” makes for a grim contrast with our own century, and the idea that we are standing at the precipice of a risky “time of perils”.